ARE THE PSYCHOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN GENDERS GREATER OR SMALLER THAN THOSE BETWEEN SEXES?

This is the question that Sixth Form pupil Keziah (M) debated in an essay which was shortlisted for a prize in the John Locke Institute Essay Competition over the summer. The John Locke Institute encourages young people to cultivate the characteristics that turn good pupils into great writers: independent thought, depth of knowledge, clear reasoning, critical analysis and persuasive style. Over 2700 essays were submitted by entrants in 80 countries for the prestigious competition and you can read Keziah’s essay here.

We’ve all heard the old wives’ tales ‘men can’t multitask’ and ‘girls are more emotional than men’ but just how true are these claims? In the modern world we live in, the perception of identity is constantly changing as the world becomes more accepting of different identities that our ancestors would have considered stereotypically incorrect. In today’s world, it is paramount to be on top of the current terms to increase our understanding and acceptance of others’ identities, yet the majority of the population are ignorant of the differences between genders and sexes – and to an extent the importance and relevance of each term individually.

It is perhaps unsuitable to give each term a single definition as it is defined differently in many cultures and individuals, yet for the sake of coming to a comprehensive conclusion in a short space I plan to do so. Psychology is the scientific study of the human mind, a very broad subject that can be broken down into levels of analysis. The biological level of analysis studies the physiological features that relate to psychological processes while the sociocultural level of analysis focuses on the relationship between the psychological processes and culture and the external environment. These are only two levels of analysis, but they are the two most prevalent in this debate so I will focus on them. For the purpose of this essay and this essay only, I will define sex as a characteristic determined at birth by an individual’s sexual organs and chromosomes. It can be split into two single categories – male (XY) and female (XX). There are of course exceptions, primarily disorders of sex development (chromosomes may be for example 45XO or 47 XXX, XXY) where the sex of a new-born is unclear, and the call is often left to the doctor on duty at the time. This can be generally termed intersex. This raises many complications answering this question which I do not dispute, however I will put this aside for this essay. Therefore, sex is a categorical characteristic determined by biology. Gender is perhaps the harder of the two to define. It can be considered a constantly developing spectrum that is not limited to the binary genders of cis-woman and cisman, but includes genders such as genderfluid, non-binary, transgender and genderqueer. Different sources claim there to be different numbers of genders ranging from 40 to 80 and an individual can associate with multiple genders hence why I am suggesting it is a dynamic spectrum. Gender does not appear to be based on biological factors but more so on sociocultural factors, and therefore it can be seen as a social construct. Despite giving these terms definitions, there is little research that recognises the importance of the difference and studies the terms individually, but instead often refers to it as sex/gender. It is important to remember that this doesn’t come from a place of naivety and ignorance for the most part, but from an inability to study the terms individually. It is impossible for a person to have a gender but not a sex or a sex but not a gender and therefore we cannot easily distinguish what characteristics are rooted in sex and which are rooted in gender. It is very rare to be able to establish a causal relationship. This proves a major obstacle in determining if the difference between genders is greater or smaller than that of sex. Gender is a social construct and so I will address the sociocultural aspect as a result of gender and the biological aspect as a result of sex, although not without careful scrutiny.

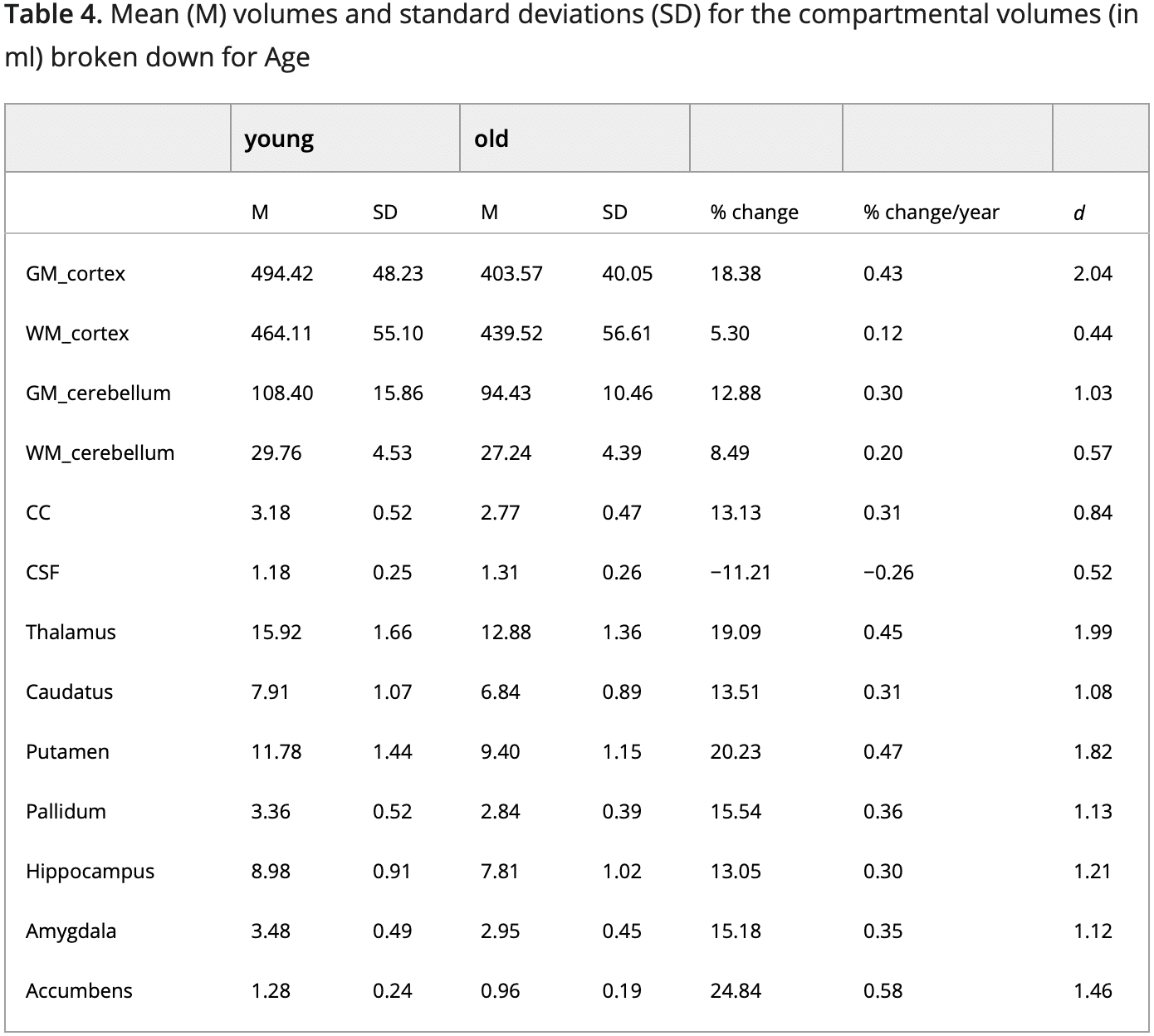

One of the most obvious differences between sexes is their sexual organs. It is also a well- known fact that men are taller, have more upper body strength and have a deeper voice than women; and women have curvy hips, an earlier onset of puberty and more body fat than men. These characteristics all have a d value over 0.8 and so are considered to have a large difference1. The size of a difference is often measured using Cohen’s d– an effect size measure2. The values of d can be categorised into small (0.02 < d < 0.50), medium (0.50 < d < 0.80) and large (d > 0.80). These physiological differences are clearly significant differences between males and females, however, they are not psychological differences and so are not directly relevant to this debate. Brain anatomy, however, is relevant as the structure of the brain directly impacts the function. Grey matter, white matter, and total brain volumes give d values between 1.00 and 1.453. Jäncke et al (2015)4 analysed T-1 weighted brain data from 856 healthy subjects (women: 452; men: 404), split into two categories based on age (young = below 45; old = above 45). The data was obtained over a period of nine years from a database of subjects examined in previously published articles. Table 1 shows their results, focusing on the d value it suggests there is a significant difference between the sexes in the anatomy of the brain. This anatomical difference between the sexes has little impact on its own, and our knowledge of the impacts these differences have is extremely limited so it is difficult to make a judgement on the significance of this difference.

Brain activation differs between sexes and an example of this can be found in the metanalysis by Stevens and Hamann5. They found that when presented with a negative emotional stimulus, women exhibited greater activation in the amygdala and other regions than men, while when they were positive emotional stimuli the men exhibited the greater activation in the amygdala. This idea can be applied to a huge range of situations and could be the causal factor for many behavioural characteristics, such as the idea that ‘women gossip’.

Hormones are another key biological factor to review. The Geschwind-Behan-Galaburda theory argues that the two hemispheres develop differently depending on the rate of testosterone (a predominantly male hormone).6,7,8 Neurological development always begins as female until genes on the Y chromosome initiate masculinising events.9 Androgen levels increasing during the second trimester of pregnancy, for example, reduce the rate of development in the left-hemisphere and stimulate increased growth in the posterior right-hemispheric regions. Testosterone is believed to be responsible for many other characteristics such as competitiveness and a high sex drive which are considered male traits. That is not to say females cannot posses these traits as females also have testosterone (in lower levels) and these traits cannot be considered dimorphic, however this shows a clear difference between the sexes.

Gender is a social construct. It is not static but a spectrum that can change as an individual matures and it can be influenced greatly by experiences. Infants are not born with predetermined gender-stereotypes and only begin to understand them at the age of three10. This is perhaps the easiest time to identify what constitutes as sex or gender, although an infant’s brain is not fully developed so this still has its downfalls. Cultural expectations of each gender, often through the medium of stereotypes, can build schemas forcing the child to conform to gender-stereotypes. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions can play a part in how gender roles are portrayed. A culture with a high power distance index (PDI) may view men as the head of the family. Alternatively, a feminine culture may value maternal instincts and have a higher respect for women. Saudi Arabia has a very high PDI (95)11 and is considered a masculine country (60) and this is reflected in their treatment of women. Women are viewed as a possession and they have only recently been given the right to drive. Although this could be argued to be due to their sex as opposed to their gender, I am classing it as the latter as it is not true for all females globally.

The sociocultural aspect can influence the biological evidence through neuroplasticity. The brain continues to change and adapt to external experiences and the environment, and anatomical sex difference within the brain can be reversed due to different environments12. Equally, the biological has influenced the sociocultural way of analysis. Looking at the Grain of Truth hypothesis for the formation of stereotypes, evidenced by Campbell (1967)13 the basis for gender-stereotypes originates from a truth, for instance ‘Girls can’t throw’ has evolved from the fact that males have a stronger throwing ability.

Enculturation plays a large part in the development of gender. Fagot (1978)14 studied 24 families to investigate if parents treated their children differently depending on their sex. She found that parents reacted more favourably when the child was engaged in same-sex preferred behaviour. The impacts of this are pretty astonishing. Take careers for example, only 15% of engineer graduates are women15, and only 16% of carers are men16. Similarly, the toys children play with, the clothing people wear and even food preference is defined by societies’ gender-stereotypes.

Scandinavia raises an interesting contradiction. Scandinavians are considered, amongst other Nordic countries, to be the most progressive people when it comes to accepting all gender identities and eliminating discrimination, yet they show some of the largest psychological variances of all. When everyone has the same rights regardless of gender, and gender-stereotypes are kept to a minimum, only genetic predispositions dictate behaviour – the characteristics of the sexes. This is referred to as the gender equality paradox.17 This could of course be argued against with reference to unconscious bias, so gender roles are still determined by society and gatekeepers such as parents influencing their children on gender roles through Social Cognitive Theory.

Hausmann et al (2009)18 examined subjects in sex-sensitive tasks after completing questionnaires that enforced gender stereotypes. In the mental rotation test males were more successful, however the control group (gender-neutral questionnaire) showed no difference between genders/sexes. The males in the gender stereotyped group had testosterone levels 60% higher than the control group males. If you consider sex hormones to be a trait of sex, and gender- stereotypes to be one of gender, there is clear overlap with the social aspect influencing the biological aspect.

It is hard to distinguish between sex and gender as it is difficult to study either individually and they constantly interact. From the viewpoint of the biological level of analysis the differences between sexes are greater than those of gender. The differences in the sexes are universal and small differences such as testosterone levels have a huge influence on the way members of different sexes think and behave. This case is aided by the evidence from Scandinavia which suggests males and females are innately different from each other, regardless of gender. Alternatively, from the sociocultural viewpoint, the difference between genders is far greater than that of sexes. Gender is dynamic and not dimorphic. Gender-stereotypes learnt at a young age can influence life decisions. It is possible that the extent to which this is true depends on each culture as every culture influences how great the gender divide is and how differently genders are treated, but this can lead to large differences such as those in Saudi Arabia. I have neglected to discuss cognitive level of analysis, however these differences are overestimated as most cognitive tasks score a very low d value19 and have little impact on the outcome of this debate. We must take great care not to disregard the interaction between gender and sex as this is continuous and impactful and can be seen clearly from studies combining factors such as Hausmann et al (2009)20. Nor can it be clear if gender or sex is truly the causal factor for most traits, as it is almost impossible to study one without interference from the other. Therefore, I strongly believe we cannot answer whether between genders are greater or smaller than those between sexes at this time. This will remain a psychological differences continuous debate between different fields in psychology until we have enough evidence to come to a more conclusive answer.

References

1 Schmitt, D. (2017, November 7). The Truth About Sex Differences. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/articles/201711/the-truth-about-sex-differences

2 Cohen, J. (n.d.). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033- 2909.112.1.155

3 Jäncke, L. (2018). Sex/gender differences in cognition, neurophysiology, and neuroanatomy. F1000Res, 7, 805. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.13917.1

4 Jäncke, L., Mérillat, S., Liem, F., & Hänggi, J. (2015). Brain size, sex, and the aging brain. Hum. Brain Mapp., 36(1), 150–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22619

5 Stevens, J. S., & Hamann, S. (2012). Sex differences in brain activation to emotional stimuli: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuropsychologia, 50(7), 1578–1593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.03.011

6 Geschwind, N. (1985a). Cerebral Lateralization. Arch Neurol, 42(5), 428. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1985.04060050026008

7 Geschwind, N. (1985b). Cerebral Lateralization. Arch Neurol, 42(6), 521. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1985.04060060019009

8 Geschwind, N. (1985c). Cerebral Lateralization. Arch Neurol, 42(7), 634. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1985.04060070024012

9 Schmitt, D. (2017, November 7). The Truth About Sex Differences. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/articles/201711/the-truth-about-sex-differences

10 Martin, C. L., & Ruble, D. N. (2010). Patterns of Gender Development. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 61(1), 353–381. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100511

11 (n.d.-b). Saudi Arabia* – Hofstede Insights. Hofstede Insights. Retrieved July 14, 2020, from https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country/saudi-arabia/

12 Jäncke, L. (2018). Sex/gender differences in cognition, neurophysiology, and neuroanatomy. F1000Res, 7, 805. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.13917.1

13 Campbell, D. T. (n.d.). Stereotypes and the perception of group differences. American Psychologist, 22(10), 817–829. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025079

14 Fagot, B. I. (1978). The Influence of Sex of Child on Parental Reactions to Toddler Children. Child Development, 49(2), 459. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128711

15 (n.d.-c). Women In STEM | STEM Women | Statistics. Retrieved July 14, 2020, from https://www.stemgraduates.co.uk/women-in-stem

16 Day, L. (2015, January 1). ‘More Male Carers Needed’ For Elderly. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-34103302

17 Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2018). The Gender-Equality Paradox in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Education. Psychol Sci, 29(4), 581–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617741719

18 Hausmann, M., Schoofs, D., Rosenthal, H. E. S., & Jordan, K. (2009). Interactive effects of sex hormones and gender stereotypes on cognitive sex differences—A psychobiosocial approach. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(3), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.09.019

19 Hyde, J. S. (n.d.). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60(6), 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.60.6.581

20 Hausmann, M., Schoofs, D., Rosenthal, H. E. S., & Jordan, K. (2009). Interactive effects of sex hormones and gender stereotypes on cognitive sex differences—A psychobiosocial approach. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(3), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.09.019